The Indonesian rupiah is the worst-performing Asian currency so far this year — and that weakness stems from the government’s decision to have the central bank partly fund its expanding budget deficit.

The “debt burden sharing” arrangement between the government and the central bank, Bank Indonesia, involves the latter buying 397.6 trillion Indonesian rupiah ($26.97 billion) worth of bonds. That debt, issued by the government, will help to finance a larger budget deficit resulting from increased spending to fight the coronavirus.

Such a program, also known as debt monetization, is likened to an unconventional tool called quantitative easing that, until recently, has only been used by major central banks in developed economies such as the U.S. and Europe.

But an increasing number of central banks in emerging markets — including Indonesia, the Philippines and South Africa — have adopted some form of quantitative easing or QE after their economies were hit hard in the pandemic.

Since Indonesia announced its version of the program last month, the rupiah has lost more than 2% of its value against the U.S. dollar as investors became worried that the move would expand the monetary base and eventually result in a weaker currency.

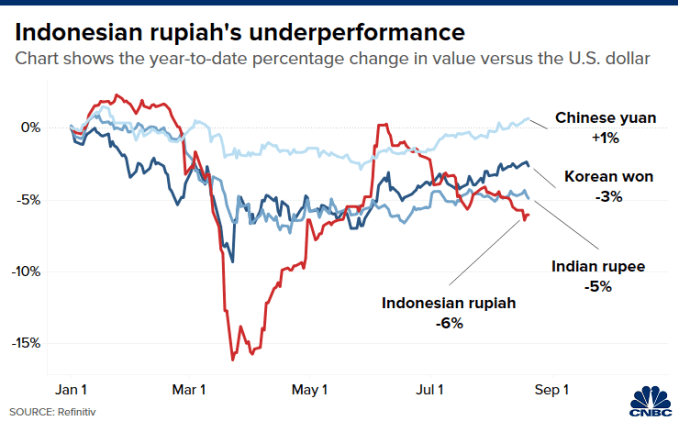

So far this year, the Indonesian rupiah has weakened by around 6% against the greenback — the worst performing currency in Asia.

“The authorities have indicated the debt monetization will be a one-off measure this year. At the same time, it does raise some questions about Indonesia’s policy approach over the medium term,” Thomas Rookmaaker, director and lead analyst for Indonesia at Fitch Ratings, said in a podcast this week

“If it were to occur repeatedly beyond this year, it would raise the potential for government interference in monetary policy making and could undermine investor confidence,” he added.

Indonesia’s version differs in several ways from how the U.S. Federal Reserve buys assets under its quantitative easing program. In particular, the Fed’s purchases are mostly done via the open market, while Bank Indonesia buys the agreed government-issued debt through private placement and won’t receive interest on those bonds.

In addition, the Indonesian central bank will be a standby buyer and help pay the interest rate for another 177 trillion rupiah ($11.9 billion) of government bonds that will be sold in auctions.

“While BI has purchased Indonesian government bonds in the past, such an explicit and transparent reference to future debt monetization and collaboration between the government and the central bank is quite surprising for an emerging market,” Pierre Chartres, fixed income investment director at M&G Investments, said a report.

“In addition, BI’s approach — aimed at reducing the interest burden for the government while maintaining higher interest rates and therefore the appeal of the debt for the pri of at leastvate sector — is also relatively innovative,” it added.

The weakness in the rupiah also comes as Indonesia — Southeast Asia’s largest economy — is struggling to contain its coronavirus outbreak.

The country has reported more than 147,200 confirmed coronavirus cases — the second-highest in Southeast Asia behind the Philippines, but its death toll of at least 6,418 is the region’s largest, according to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. The extent of Indonesia’s outbreak could be a lot worse given the country’s lack of testing for the virus,reported Reuters.

Indonesia’s economy has suffered. It shrank by 5.3% in the second quarter from a year ago — the country’s first economic contraction in more than two decades. The central bank still has room to cut interest rates to boost the economy, but it left rates unchanged during its latest meeting on Wednesday in part to prevent its currency from sliding further, analysts said.

Bank Indonesia, in a statement, said the rupiah is now “fundamentally undervalued” and could appreciate from current levels. But analysts said the future of the debt monetization program will affect the currency’s trajectory.

HSBC economist Joseph Incalcaterra said Indonesian President Joko Widodo had suggested that the government will finance next year’s budget “in cooperation with the central bank” — indicating that the debt monetization program could continue beyond 2020.

“Fortunately, conventional metrics suggest the outlook for the rupiah is otherwise strong,” Incalcaterra wrote in a Wednesday note after the central bank decision to hold rates steady.

“In the meantime, we await further communication from BI outlining conditions pertaining to an exit policy from its QE program, as well as any possible limits on direct government financing next year. Such communication will likely help ease market concerns about the future direction of the rupiah.”